What type of cartilage is converted to bone?

Open access peer-reviewed chapter

Bone Development and Growth

Submitted: September 12th, 2018 Reviewed: November 8th, 2018 Published: Dec 14th, 2018

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.82452

IntechOpen Downloads

5,786

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Altmetric score

Overall attention for this chapters

Abstruse

The process of bone formation is chosen osteogenesis or ossification. Later on progenitor cells course osteoblastic lines, they proceed with three stages of evolution of cell differentiation, chosen proliferation, maturation of matrix, and mineralization. Based on its embryological origin, there are ii types of ossification, called intramembranous ossification that occurs in mesenchymal cells that differentiate into osteoblast in the ossification middle directly without prior cartilage formation and endochondral ossification in which os tissue mineralization is formed through cartilage germination beginning. In intramembranous ossification, os development occurs straight. In this procedure, mesenchymal cells proliferate into areas that have high vascularization in embryonic connective tissue in the formation of prison cell condensation or primary ossification centers. This cell will synthesize bone matrix in the periphery and the mesenchymal cells continue to differentiate into osteoblasts. After that, the bone will be reshaped and replaced by mature lamellar os. Endochondral ossification volition form the center of primary ossification, and the cartilage extends past proliferation of chondrocytes and deposition of cartilage matrix. After this formation, chondrocytes in the central region of the cartilage outset to proceed with maturation into hypertrophic chondrocytes. After the chief ossification center is formed, the marrow crenel begins to expand toward the epiphysis. So the subsequent stages of endochondral ossification will take identify in several zones of the bone.

Keywords

- osteogenesis

- ossification

- bone germination

- intramembranous ossification

- endochondral ossification

*Address all correspondence to: dr_setia76@yahoo.co.id

1. Introduction

Bone is living tissue that is the hardest among other connective tissues in the torso, consists of 50% h2o. The solid part residual consisting of various minerals, especially 76% of calcium salt and 33% of cellular material. Os has vascular tissue and cellular action products, especially during growth which is very dependent on the blood supply as bones source and hormones that greatly regulate this growth procedure. Bone-forming cells, osteoblasts, osteoclast play an important role in determining bone growth, thickness of the cortical layer and structural arrangement of the lamellae.

Bone continues to change its internal structure to reach the functional needs and these changes occur through the activity of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. The bone seen from its development can exist divided into 2 processes: start is the intramembranous ossification in which bones form directly in the form of primitive mesenchymal connective tissue, such as the mandible, maxilla and skull bones. Second is the endochondral ossification in which bone tissue replaces a preexisting hyaline cartilage, for example during skull base formation. The aforementioned formative cells form 2 types of bone formation and the terminal structure is not much different.

Bone growth depends on genetic and ecology factors, including hormonal effects, diet and mechanical factors. The growth charge per unit is not always the same in all parts, for case, faster in the proximal end than the distal humerus considering the internal pattern of the spongiosum depends on the management of os pressure. The direction of bone formation in the epiphysis plane is determined by the direction and distribution of the pressure line. Increased thickness or width of the bone is caused by degradation of new os in the grade of circumferential lamellae under the periosteum. If bone growth continues, the lamella volition be embedded behind the new bone surface and be replaced by the haversian canal system.

Ad

2. Bone cells and matrix

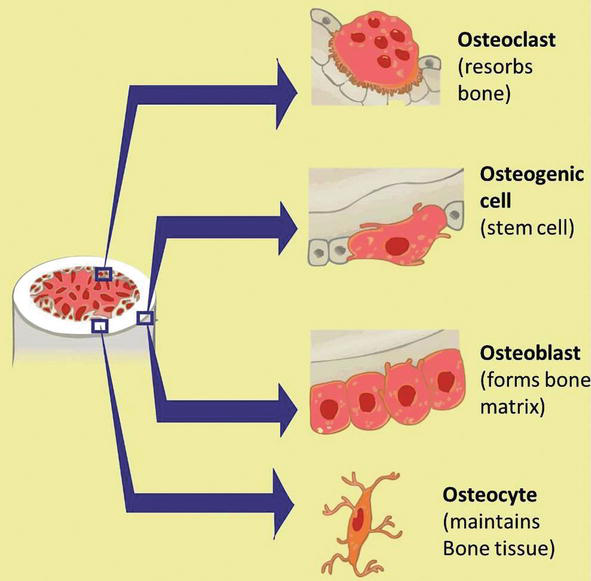

Os is a tissue in which the extracellular matrix has been hardened to suit a supporting role. The key components of bone, like all connective tissues, are cells and matrix. Although os cells compose a pocket-size amount of the bone volume, they are crucial to the function of basic. Four types of cells are found inside bone tissue: osteoblasts, osteocytes, osteogenic cells, and osteoclasts. They each unique functions and are derived from two different cell lines (Figure one and Table 1) [1, two, 3, 4, 5, six, seven].

-

Osteoblast synthesizes the bone matrix and are responsible for its mineralization. They are derived from osteoprogenitor cells, a mesenchymal stem cell line.

-

Osteocytes are inactive osteoblasts that take go trapped inside the bone they have formed.

-

Osteoclasts interruption down bone matrix through phagocytosis. Predictably, they ruffled edge, and the infinite betwixt the osteoblast and the bone is known as Howship's lacuna.

Figure i.

Development of bone precursor cells. Bone precursor cells are divided into developmental stages, which are 1. mesenchymal stalk cell, ii. pre-osteoblast, 3. osteoblast, and iv. mature osteocytes, and v. osteoclast.

Tabular array one.

Bone cells, their function, and locations [i, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, seven].

The balance between osteoblast and osteoclast activity governs os turnover and ensures that bone is neither overproduced nor overdegraded. These cells build upwards and pause down bone matrix, which is equanimous of:

-

Osteoid, which is the unmineralized matrix equanimous of type I collagen and gylcosaminoglycans (GAGs).

-

Calcium hydroxyapatite, a calcium salt crystal that give bone its strength and rigidity.

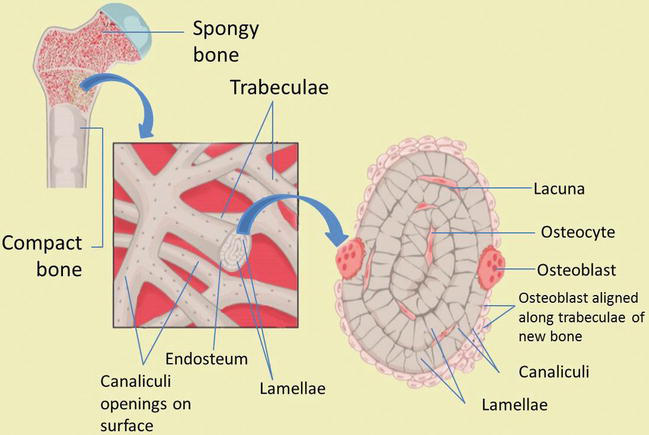

Bone is divided into two types that are different structurally and functionally. Most bones of the torso consist of both types of bone tissue (Figure two) [1, 2, 8, 9]:

-

Compact bone, or cortical bone, mainly serves a mechanical function. This is the area of bone to which ligaments and tendons attach. It is thick and dense.

-

Trabecular os, also known every bit cancellous bone or spongy os, mainly serves a metabolic function. This blazon of bone is located between layers of meaty bone and is thin porous. Location within the trabeculae is the bone marrow.

Figure 2.

Structure of a long bone.

Ad

3. Bone structure

3.1 Macroscopic bone structure

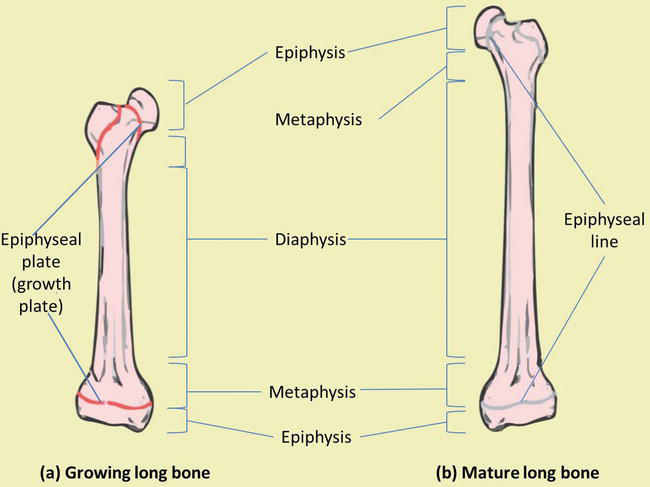

Long basic are composed of both cortical and cancellous os tissue. They consist of several areas (Figure iii) [3, four]:

-

The epiphysis is located at the end of the long os and is the parts of the os that participate in joint surfaces.

-

The diaphysis is the shaft of the bone and has walls of cortical os and an underlying network of trabecular bone.

-

The epiphyseal growth plate lies at the interface between the shaft and the epiphysis and is the region in which cartilage proliferates to crusade the elongation of the bone.

-

The metaphysis is the area in which the shaft of the bone joins the epiphyseal growth plate.

Figure 3.

Os macrostructure. (a) Growing long bone showing epiphyses, epiphyseal plates, metaphysis and diaphysis. (b) Mature long bone showing epiphyseal lines.

Different areas of the os are covered past unlike tissue [iv]:

-

The epiphysis is lined by a layer of articular cartilage, a specialized form of hyaline cartilage, which serves equally protection against friction in the joints.

-

The outside of the diaphysis is lined by periosteum, a fibrous external layer onto which muscles, ligaments, and tendons attach.

-

The inside of the diaphysis, at the border between the cortical and cancellous os and lining the trabeculae, is lined by endosteum.

3.2 Microscopic os structure

Compact bone is organized every bit parallel columns, known every bit Haversian systems, which run lengthwise down the axis of long bones. These columns are composed of lamellae, concentric rings of bone, surrounding a primal channel, or Haversian canal, that contains the nerves, blood vessels, and lymphatic system of the bone. The parallel Haversian canals are continued to one another by the perpendicular Volkmann's canals.

The lamellae of the Haversian systems are created by osteoblasts. Equally these cells secrete matrix, they become trapped in spaces called lacunae and become known every bit osteocytes. Osteocytes communicate with the Haversian culvert through cytoplasmic extensions that run through canaliculi, small interconnecting canals (Effigy 4) [1, ii, viii, ix]:

Figure four.

Os microstructure. Compact and spongy os structures.

The layers of a long os, outset at the external surface, are therefore:

-

Periosteal surface of meaty os

-

Outer circumferential lamellae

-

Compact bone (Haversian systems)

-

Inner circumferential lamellae

-

Endosteal surface of compact os

-

Trabecular bone

Ad

4. Bone germination

Os development begins with the replacement of collagenous mesenchymal tissue past os. This results in the formation of woven os, a primitive grade of os with randomly organized collagen fibers that is further remodeled into mature lamellar bone, which possesses regular parallel rings of collagen. Lamellar bone is and then constantly remodeled by osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Based on the evolution of bone formation can be divided into two parts, called endochondral and intramembranous bone formation/ossification [1, 2, iii, eight].

four.1 Intramembranous bone formation

During intramembranous bone formation, the connective tissue membrane of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells changes into bone and matrix bone cells [10]. In the craniofacial cartilage basic, intramembranous ossification originates from nerve crest cells. The earliest evidence of intramembranous bone formation of the skull occurs in the mandible during the sixth prenatal week. In the eighth week, reinforcement centre appears in the calvarial and facial areas in areas where there is a balmy stress strength [eleven].

Intramembranous bone germination is found in the growth of the skull and is as well found in the sphenoid and mandible even though it consists of endochondral elements, where the endochondral and intramembranous growth process occurs in the same os. The basis for either bone formation or bone resorption is the same, regardless of the type of membrane involved.

Sometimes according to where the germination of bone tissue is classified as "periosteal" or "endosteal". Periosteal bone always originates from intramembranous, but endosteal os can originate from intramembranous as well as endochondral ossification, depending on the location and the way information technology is formed [3, 12].

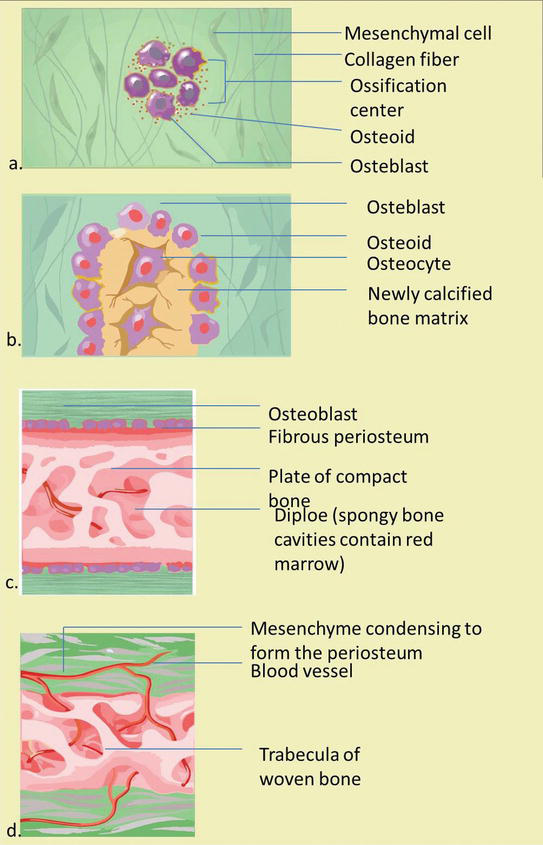

4.one.1 The stage of intramembranous bone formation

The argument below is the stage of intramembrane bone germination (Figure 5) [3, 4, 11, 12]:

-

An ossification center appears in the fibrous connective tissue membrane. Mesenchymal cells in the embryonic skeleton assemble together and begin to differentiate into specialized cells. Some of these cells differentiate into capillaries, while others will get osteogenic cells and osteoblasts, and then forming an ossification heart.

-

Bone matrix (osteoid) is secreted within the fibrous membrane. Osteoblasts produce osteoid tissue, by means of differentiating osteoblasts from the ectomesenchyme condensation center and producing bone fibrous matrix (osteoid). Then osteoid is mineralized within a few days and trapped osteoblast become osteocytes.

-

Woven bone and periosteum form. The encapsulation of cells and blood vessels occur. When osteoid degradation past osteoblasts continues, the encased cells develop into osteocytes. Accumulating osteoid is laid downwards between embryonic blood vessels, which course a random network (instead of lamellae) of trabecular. Vascularized mesenchyme condenses on external face up of the woven bone and becomes the periosteum.

-

Product of osteoid tissue by membrane cells: osteocytes lose their ability to contribute directly to an increase in bone size, simply osteoblasts on the periosteum surface produce more osteoid tissue that thickens the tissue layer on the existing bone surface (for instance, appositional bone growth). Formation of a woven bone neckband that is afterwards replaced by mature lamellar os. Spongy bone (diploe), consisting of distinct trabeculae, persists internally and its vascular tissue becomes carmine marrow.

-

Osteoid calcification: The occurrence of bone matrix mineralization makes bones relatively impermeable to nutrients and metabolic waste material. Trapped blood vessels function to supply nutrients to osteocytes as well as bone tissue and eliminate waste product products.

-

The formation of an essential membrane of bone which includes a membrane exterior the bone called the os endosteum. Bone endosteum is very important for bone survival. Disruption of the membrane or its vascular tissue tin can cause bone cell death and os loss. Bones are very sensitive to pressure. The calcified bones are difficult and relatively inflexible.

Figure five.

The stage of intramembranous ossification. The following stages are (a) Mesenchymal cells group into clusters, and ossification centers form. (b) Secreted osteoid traps osteoblasts, which then become osteocytes. (c) Trabecular matrix and periosteum form. (d) Compact bone develops superficial to the trabecular os, and crowded blood vessels condense into cerise marrow.

The matrix or intercellular substance of the bone becomes calcified and becomes a bone in the cease. Bone tissue that is found in the periosteum, endosteum, suture, and periodontal membrane (ligaments) is an example of intramembranous bone germination [3, 13].

Intramembranous os formation occurs in ii types of bone: bundle os and lamellar os. The bone parcel develops directly in connective tissue that has not been calcified. Osteoblasts, which are differentiated from the mesenchyme, secrete an intercellular substance containing collagen fibrils. This osteoid matrix calcifies past precipitating apatite crystals. Primary ossification centers only prove minimal bone calcification density. The apatite crystal deposits are mostly irregular and structured like nets that are contained in the medullary and cortical regions. Mineralization occurs very quickly (several tens of thousands of millimeters per day) and can occur simultaneously in large areas. These apatite deposits increment with time. Os tissue is only considered mature when the crystalized area is arranged in the same direction as collagen fibrils.

Bone tissue is divided into 2, chosen the outer cortical and medullary regions, these two areas are destroyed by the resorption procedure; which goes along with further bone formation. The surrounding connective tissue volition differentiate into the periosteum. The lining in the periosteum is rich in cells, has osteogenic function and contributes to the formation of thick bones as in the endosteum.

In adults, the bundle bone is usually only formed during rapid bone remodeling. This is reinforced by the presence of lamellar os. Unlike bundle bone formation, lamellar os evolution occurs merely in mineralized matrix (east.thou., cartilage that has calcified or bundle os spicules). The nets in the bone bundle are filled to strengthen the lamellar bone, until meaty os is formed. Osteoblasts appear in the mineralized matrix, which then course a circumvolve with intercellular matter surrounding the key vessels in several layers (Haversian system). Lamella bone is formed from 0.7 to 1.5 microns per twenty-four hour period. The network is formed from complex cobweb arrangements, responsible for its mechanical properties. The arrangement of apatites in the concentric layer of fibrils finally meets functional requirements. Lamellar bone depends on ongoing deposition and resorption which can be influenced past ecology factors, 1 of this which is orthodontic treatment.

4.1.2 Factors that influence intramembranous os formation

Intramembranous bone formation from desmocranium (suture and periosteum) is mediated past mesenchymal skeletogenetic structures and is achieved through os degradation and resorption [eight]. This development is virtually entirely controlled through local epigenetic factors and local environmental factors (i.due east. by muscle strength, external local force per unit area, brain, eyes, tongue, fretfulness, and indirectly past endochondral ossification). Genetic factors only have a nonspecific morphogenetic effect on intramembranous bone formation and merely decide external limits and increment the number of growth periods. Anomaly disorder (especially genetically produced) tin can affect endochondral os formation, and so local epigenetic factors and local environmental factors, including steps of orthodontic therapy, tin can directly touch on intramembranous os formation [iii, 11].

4.2 Endochondral os formation

During endochondral ossification, the tissue that will become bone is firstly formed from cartilage, separated from the articulation and epiphysis, surrounded by perichondrium which then forms the periosteum [11]. Based on the location of mineralization, it tin can exist divided into: Perichondral Ossification and Endochondral Ossification. Both types of ossification play an essential function in the formation of long basic where just endochondral ossification takes place in brusque bones. Perichondral ossification begins in the perichondrium. Mesenchymal cells from the tissue differentiate into osteoblasts, which surround bony diaphyseal before endochondral ossification, indirectly touch on its direction [three, eight, 12]. Cartilage is transformed into bone is craniofacial bone that forms at the eigth prenatal week. Only bone on the cranial base and part of the skull bone derived from endochondral bone formation. Regarding to differentiate endochondral bone germination from chondrogenesis and intramembranous bone formation, five sequences of bone formation steps were determined [3].

4.2.one The stages of endochondral os formation

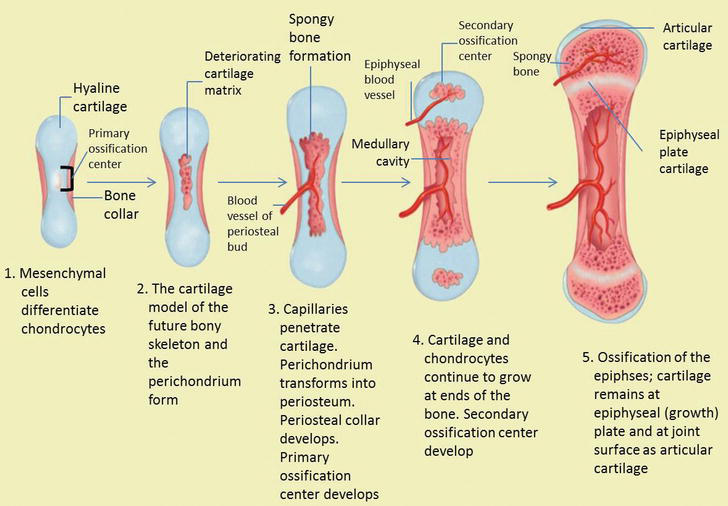

The statements below are the stages of endochondral bone germination (Effigy six) [four, 12]:

-

Mesenchymal cells grouping to grade a shape template of the futurity bone.

-

Mesenchymal cells differentiate into chondrocytes (cartilage cells).

-

Hypertrophy of chondrocytes and calcified matrix with calcified central cartilage primordium matrix formed. Chondrocytes bear witness hypertrophic changes and calcification from the cartilage matrix continues.

-

Entry of blood vessels and connective tissue cells. The nutrient artery supplies the perichondrium, breaks through the nutrient foramen at the mid-region and stimulates the osteoprogenitor cells in the perichondrium to produce osteoblasts, which changes the perichondrium to the periosteum and starts the formation of ossification centers.

-

The periosteum continues its development and the partition of cells (chondrocytes) continues as well, thereby increasing matrix production (this helps produce more length of bone).

-

The perichondrial membrane surrounds the surface and develops new chondroblasts.

-

Chondroblasts produce growth in width (appositional growth).

-

Cells at the center of the cartilage lyse (break autonomously) triggers calcification.

Effigy half dozen.

The stage of endochondral ossification. The following stages are: (a) Mesenchymal cells differentiate into chondrocytes. (b) The cartilage model of the time to come bony skeleton and the perichondrium form. (c) Capillaries penetrate cartilage. Perichondrium transforms into periosteum. Periosteal collar develops. Master ossification eye develops. (d) Cartilage and chondrocytes go on to grow at ends of the os. (e) Secondary ossification centers develop. (f) Cartilage remains at epiphyseal (growth) plate and at joint surface every bit articular cartilage.

During endochondral bone formation, mesenchymal tissue firstly differentiates into cartilage tissue. Endochondral bone germination is morphogenetic accommodation (normal organ development) which produces continuous bone in certain areas that are prominently stressed. Therefore, this endochondral bone formation can be institute in the bones associated with joint movements and some parts of the skull base. In hypertrophic cartilage cells, the matrix calcifies and the cells undergo degeneration. In cranial synchondrosis, in that location is proliferation in the formation of bones on both sides of the bone plate, this is distinguished by the germination of long bone epiphyses which just occurs on ane side but [2, 14].

As the cartilage grows, capillaries penetrate information technology. This penetration initiates the transformation of the perichondrium into the bone-producing periosteum. Here, the osteoblasts course a periosteal neckband of compact os around the cartilage of the diaphysis. Past the second or tertiary month of fetal life, bone jail cell development and ossification ramps upwardly and creates the

While these deep changes occur, chondrocytes and cartilage continue to grow at the ends of the os (the future epiphyses), which increase the os length and at the aforementioned fourth dimension bone also replaces cartilage in the diaphysis. By the fourth dimension the fetal skeleton is fully formed, cartilage only remains at the articulation surface as articular cartilage and betwixt the diaphysis and epiphysis as the epiphyseal plate, the latter of which is responsible for the longitudinal growth of bones. Subsequently birth, this same sequence of events (matrix mineralization, decease of chondrocytes, invasion of blood vessels from the periosteum, and seeding with osteogenic cells that get osteoblasts) occur in the epiphyseal regions, and each of these centers of activity is referred to as a

At that place are 4 of import things about cartilage in endochondral os germination:

-

Cartilage has a rigid and firm structure, but not usually calcified nature, giving three basic functions of growth (a) its flexibility can support an advisable network construction (nose), (b) force per unit area tolerance in a particular place where pinch occurs, (c) the location of growth in conjunction with enlarging bone (synchondrosis of the skull base of operations and condyle cartilage).

-

Cartilage grows in ii adjacent places (by the activity of the chondrogenic membrane) and grows in the tissues (chondrocyte cell sectionalization and the add-on of its intercellular matrix).

-

Bone tissue is not the same every bit cartilage in terms of its tension adaptation and cannot grow direct in areas of high compression because its growth depends on the vascularization of bone germination covering the membrane.

-

Cartilage growth arises where linear growth is required toward the force per unit area direction, which allows the bone to lengthen to the area of strength and has not however grown elsewhere past membrane ossification in conjunction with all periosteal and endosteal surfaces.

4.2.2 Factors that influence endochondral ossification

Membrane disorders or vascular supply problem of these essential membranes can directly result in bone cell death and ultimately os impairment. Calcified bones are generally hard and relatively inflexible and sensitive to pressure [12].

Cranial synchondrosis (e.yard., spheno ethmoidal and spheno occipital growth) and endochondral ossification are further adamant past chondrogenesis. Chondrogenesis is mainly influenced by genetic factors, similar to facial mesenchymal growth during initial embryogenesis to the differentiation phase of cartilage and cranial bone tissue.

This process is only slightly afflicted by local epigenetic and environmental factors. This can explain the fact that the cranial base is more resistant to deformation than desmocranium. Local epigenetic and ecology factors cannot trigger or inhibit the amount of cartilage formation. Both of these have trivial effect on the shape and direction of endochondral ossification. This has been analyzed especially during mandibular condyle growth.

Local epigenetics and environmental factors merely affect the shape and management of cartilage formation during endochondral ossification Because the fact that condyle cartilage is a secondary cartilage, it is assumed that local factors provide a greater influence on the growth of mandibular condyle.

four.2.3 Chondrogenesis

Chondrogenesis is the process by which cartilage is formed from condensed mesenchyme tissue, which differentiates into chondrocytes and begins secreting the molecules that form the extracellular matrix [5, 14].

The statement below is v steps of chondrogenesis [8, xiv]:

-

Chondroblasts produce a matrix: the extracellular matrix produced by cartilage cells, which is firm but flexible and capable of providing a rigid support.

-

Cells become embed in a matrix: when the chondroblast changes to exist completely embed in its own matrix fabric, cartilage cells turn into chondrocytes. The new chondroblasts are distinguished from the membrane surface (perichondrium), this will result in the improver of cartilage size (cartilage tin can increase in size through apposition growth).

-

Chondrocytes enlarge, dissever and produce a matrix. Cell growth continues and produces a matrix, which causes an increase in the size of cartilage mass from within. Growth that causes size increase from the inside is called interstitial growth.

-

The matrix remains uncalcified: cartilage matrix is rich of chondroitin sulfate which is associated with not-collagen proteins. Nutrition and metabolic waste material are discharged directly through the soft matrix to and from the cell. Therefore, blood vessels aren't needed in cartilage.

-

The membrane covers the surface but is not essential: cartilage has a closed membrane vascularization called perichondrium, but cartilage can exist without whatsoever of these. This property makes cartilage able to grow and adapt where it needs pressure (in the joints), then that cartilage can receive pressure.

Endochondral ossification begins with feature changes in cartilage bone cells (hypertrophic cartilage) and the surroundings of the intercellular matrix (calcium laying), the formation which is chosen every bit primary spongiosa. Blood vessels and mesenchymal tissues then penetrate into this surface area from the perichondrium. The binding tissue cells then differentiate into osteoblasts and cells. Chondroblasts erode cartilage in a cave-like blueprint (cavity). The remnants of mineralized cartilage the central office of laying the lamellar bone layer.

The osteoid layer is deposited on the calcified spicules remaining from the cartilage so mineralized to class spongiosa os, with fine reticular structures that resemble nets that possess cartilage fragments between the spicular basic. Spongy bones tin turn into compact bones past filling empty cavities. Both endochondral and perichondral bone growth both have place toward epiphyses and joints. In the bone lengthening process during endochondral ossification depends on the growth of epiphyseal cartilage. When the epiphyseal line has been airtight, the bone volition non increase in length. Unlike os, cartilage bone growth is based on apposition and interstitial growth. In areas where cartilage bone is covered past os, diverse variations of zone characteristics, based on the developmental stages of each individual, can differentiate which then continuously merge with each other during the conversion procedure. Environmental influences (co: mechanism of orthopedic functional tools) accept a potent effect on condylar cartilage because the bone is located more superficially [v].

Advertisement

5. Bone growth

Cartilage bone height development occurs during the third month of intra uterine life. Cartilage plate extends from the nasal bone capsule posteriorly to the foramen magnum at the base of the skull. It should be noted that cartilages which close to avascular tissue accept internal cells obtained from the diffusion process from the outermost layer. This means that the cartilage must be flatter. In the early stages of evolution, the size of a very small embryo can form a chondroskeleton easily in which the further growth preparation occurs without internal claret supply [one].

During the 4th calendar month in the uterus, the development of vascular elements to various points of the chondrocranium (and other parts of the early cartilage skeleton) becomes an ossification center, where the cartilage changes into an ossification center, and bone forms around the cartilage. Cartilage continues to grow chop-chop but information technology is replaced past os, resulting in the rapid increment of bone amount. Finally, the onetime chondrocranium amount will decrease in the expanse of cartilage and large portions of bone, assumed to exist typical in ethmoid, sphenoid, and basioccipital bones. The cartilage growth in relation to skeletal bone is like as the growth of the limbs [1, 3].

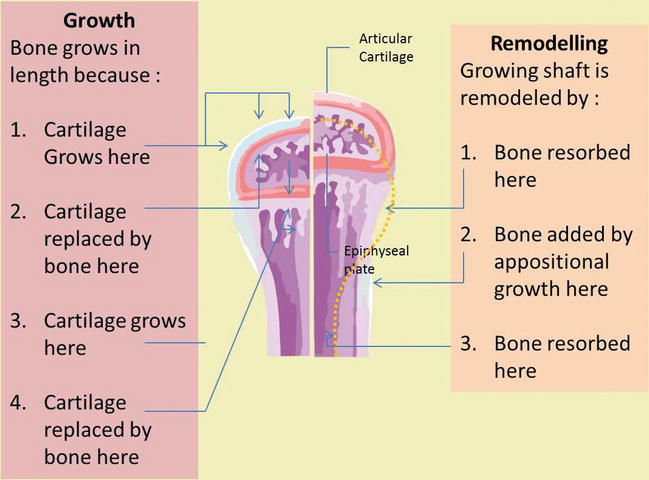

Longitudinal bone growth is accompanied by remodeling which includes appositional growth to thicken the bone. This process consists of bone germination and reabsorption. Bone growth stops around the age of 21 for males and the age of 18 for females when the epiphyses and diaphysis have fused (epiphyseal plate closure).

Normal bone growth is dependent on proper dietary intake of poly peptide, minerals and vitamins. A deficiency of vitamin D prevents calcium absorption from the GI tract resulting in rickets (children) or osteomalacia (adults). Osteoid is produced only calcium salts are not deposited, and then bones soften and weaken.

five.1 Oppositional os growth

At the length of the long basic, the reinforcement plane appears in the middle and at the end of the bone, finally produces the fundamental axis that is called the diaphysis and the bony cap at the stop of the bone is called the epiphysis. Between epiphyses and diaphysis is a calcified area that is not calcified called the epiphyseal plate. Epiphyseal plate of the long bone cartilage is a major center for growth, and in fact, this cartilage is responsible for almost all the long growths of the bones. This is a layer of hyaline cartilage where ossification occurs in immature bones. On the epiphyseal side of the epiphyseal plate, the cartilage is formed. On the diaphyseal side, cartilage is ossified, and the diaphysis so grows in length. The epiphyseal plate is composed of five zones of cells and activeness [3, 4].

Near the outer end of each epiphyseal plate is the active zone dividing the cartilage cells. Some of them, pushed toward diaphysis with proliferative action, develop hypertrophy, secrete an extracellular matrix, and finally the matrix begins to fill with minerals and then is quickly replaced by bone. As long as cartilage cells multiply growth will continue. Finally, toward the cease of the normal growth period, the rate of maturation exceeds the proliferation level, the latter of the cartilage is replaced by os, and the epiphyseal plate disappears. At that time, os growth is consummate, except for surface changes in thickness, which can be produced by the periosteum [4]. Bones proceed to grow in length until early adulthood. The lengthening is stopped in the end of adolescence which chondrocytes cease mitosis and plate thins out and replaced past bone, and then diaphysis and epiphyses fuse to be one bone (Figure seven). The rate of growth is controlled by hormones. When the chondrocytes in the epiphyseal plate cease their proliferation and os replaces the cartilage, longitudinal growth stops. All that remains of the epiphyseal plate is the epiphyseal line. Epiphyseal plate closure volition occur in eighteen-year old females or 21-twelvemonth old males.

Figure seven.

Oppositional bone growth and remodeling. The epiphyseal plate is responsible for longitudinal bone growth.

5.1.1 Epiphyseal plate growth

The cartilage found in the epiphyseal gap has a divers hierarchical structure, directly beneath the secondary ossification center of the epiphysis. By shut examination of the epiphyseal plate, it appears to exist divided into five zones (starting from the epiphysis side) (Effigy 8) [iv]:

-

The resting zone: it contains hyaline cartilage with few chondrocytes, which means no morphological changes in the cells.

-

The proliferative zone: chondrocytes with a higher number of cells carve up speedily and course columns of stacked cells parallel to the long axis of the bone.

-

The hypertrophic cartilage zone: information technology contains big chondrocytes with cells increasing in book and modifying the matrix, effectively elongating bone whose cytoplasm has accumulated glycogen. The resorbed matrix is reduced to thin septa between the chondrocytes.

-

The calcified cartilage zone: chondrocytes undergo apoptosis, the sparse septa of cartilage matrix become calcified.

-

The ossification zone: endochondral bone tissue appears. Blood capillaries and osteoprogenitor cells (from the periosteum) invade the cavities left past the chondrocytes. The osteoprogenitor cells form osteoblasts, which deposit bone matrix over the three-dimensional calcified cartilage matrix.

Figure 8.

Epiphyseal plate growth. Five zones of epiphyseal growth plate includes: 1. resting zone, 2. proliferation zone, 3. hypertrophic cartilage zone, iv. calcified cartilage zone, and 5. ossification zone.

five.2 Appositional bone growth

When bones are increasing in length, they are too increasing in bore; diameter growth can continue even after longitudinal growth stops. This is called appositional growth. The bone is captivated on the endosteal surface and added to the periosteal surface. Osteoblasts and osteoclasts play an essential role in appositional bone growth where osteoblasts secrete a bone matrix to the external bone surface from diaphysis, while osteoclasts on the diaphysis endosteal surface remove os from the internal surface of diaphysis. The more than bone around the medullary crenel is destroyed, the more yellowish marrow moves into empty space and fills space. Osteoclasts resorb the old bone lining the medullary cavity, while osteoblasts through intramembrane ossification produce new bone tissue beneath the periosteum. Periosteum on the bone surface also plays an important part in increasing thickness and in reshaping the external profile. The erosion of old bone along the medullary crenel and new bone deposition under the periosteum not simply increases the diameter of the diaphysis but likewise increases the diameter of the medullary cavity. This process is chosen modeling (Figure 9) [iii, 4, xv].

Figure 9.

Appositional bone growth. Os deposit past osteoblast every bit bone resorption past osteoclast.

Ad

6. The office of mesenchymal stem cell migration and differentiation in bone formation

Recent enquiry reported that os microstructure is likewise the principle of bone function, which regulates its mechanical function. Bone tissue function influenced by many factors, such equally hormones, growth factors, and mechanical loading. The microstructure of bone tissue is distribution and alignment of biological apatite (BAp) crystallites. This is determined by the direction of os prison cell behavior, for case cell migration and jail cell regulation. Ozasa et al. found that artificial control the management of mesenchymal stem cell (MSCs) migration and osteoblast alignment can reconstruct os microstructure, which guide an advisable bone formation during os remodeling and regeneration [xvi].

Bone development begins with the replacement of collagenous mesenchymal tissue by bone. Generally, bone is formed by endochondral or intramembranous ossification. Intramembranous ossification is essential in the bone such equally skull, facial bones, and pelvis which MSCs straight differentiate to osteoblasts. While, endochondral ossification plays an important role in almost bones in the homo skeleton, including long, curt, and irregular bones, which MSCs firstly experience to condensate so differentiate into chondrocytes to form the cartilage growth plate and the growth plate is so gradually replaced by new bone tissue [3, 8, 12].

MSC migration and differentiation are two of import physiological processes in os formation. MSCs migration heighten as an essential step of os formation considering MSCs initially need to migrate to the bone surface and and so contribute in bone germination process, although MSCs differentiation into osteogenic cells is besides crucial. MSC migration during bone formation has attracted more attention. Some studies show that MSC migration to the os surface is crucial for bone germination [17]. Bone marrow and periosteum are the main sources of MSCs that participate in os formation [eighteen].

In the intramembranous ossification, MSCs undergo proliferation and differentiation along the osteoblastic lineage to form os directly without first forming cartilage. MSC and preosteoblast migration is involved in this process and are mediated by plentiful factors in vivo and in vitro. MSCs initially differentiate into preosteoblasts which proliferate near the bone surface and secrete ALP. So they get mature osteoblasts and then form osteocytes which embedded in an extracellular matrix (ECM). Other factors besides regulate the intramembranous ossification of MSCs such as Runx2, special AT-rich sequence binding protein 2 (SATB 2), and Osterix every bit well every bit pathways, similar the wnt/β-catenin pathway and os morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathway [17, 19].

In the endochondral ossification, MSCs are starting time condensed to initiate cartilage model germination. The process is mediated by BMPs through phosphorylating and activating receptor SMADs to transduce signals. During condensation, the central role of MSCs differentiates into chondrocytes and secretes cartilage matrix. While, other cells in the periphery, form the perichondrium that continues expressing type I collagen and other important factors, such as proteoglycans and ALP. Chondrocytes undergo rapid proliferation. Chondrocytes in the center become maturation, accompanied with an invasion of hypertrophic cartilage past the vasculature, followed by differentiation of osteoblasts within the perichondrium and marrow cavity. The inner perichondrium cells differentiate into osteoblasts, which secrete bone matrix to form the bone collar after vascularization in the hypertrophic cartilage. Many factors that regulate endochondral ossification are growth factors (GFs), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), Sry-related high-mobility group box 9 (Sox9) and Cell-to-jail cell interaction [17, nineteen].

Advertisement

7. Conclusions

-

Osteogenesis/ossification is the procedure in which new layers of bone tissue are placed by osteoblasts.

-

During bone formation, woven bone (haphazard arrangement of collagen fibers) is remodeled into lamellar bones (parallel bundles of collagen in a layer known as lamellae)

-

Periosteum is a connective tissue layer on the outer surface of the bone; the endosteum is a sparse layer (by and large only 1 layer of cell) that coats all the internal surfaces of the bone

-

Major cell of os include: osteoblasts (from osteoprogenitor cells, forming osteoid that allow matrix mineralization to occur), osteocytes (from osteoblasts; closed to lacunae and retaining the matrix) and osteoclasts (from hemopoietic lineages; locally erodes matrix during bone formation and remodeling.

-

The process of bone formation occurs through two basic mechanisms:

-

Intramembranous bone germination occurs when bone forms inside the mesenchymal membrane. Bone tissue is directly laid on primitive connective tissue referred to mesenchyma without intermediate cartilage involvement. It forms bone of the skull and jaw; peculiarly but occurs during development likewise as the fracture repair.

-

Endochondral os formation occurs when hyaline cartilage is used every bit a precursor to os germination, and so os replaces hyaline cartilage, forms and grows all other bones, occurs during development and throughout life.

-

-

During interstitial epiphyseal growth (elongation of the os), the growth plate with zonal organization of endochondral ossification, allows bone to lengthen without epiphyseal growth plates enlarging zones include:

-

Zone of resting.

-

Zone of proliferation.

-

Zone of hypertrophy.

-

Zone of calcification.

-

Zone of ossification and resorption.

-

-

During appositional growth, osteoclasts resorb old bone that lines the medullary cavity, while osteoblasts, via intramembranous ossification, produce new bone tissue beneath the periosteum.

-

Mesenchymal stem cell migration and differentiation are two important physiological processes in os formation.

Advertisement

Acknowledgments

The writer is grateful to Zahrona Kusuma Dewi for assistance with preparation of the manuscript.

Advertizing

Disharmonize of interest

The authors declare that there is no disharmonize of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Advertisement

Acronyms and abbreviations

alkaline metal phosphatase

biological apatite

os morphogenetic protein

extracellular matrix

growth factors

mesenchymal stem cells

runt-related transcription factor 2

special AT-rich sequence binding protein two

sry-related high-mobility group box 9

transforming growth cistron-β

References

- 1.

Vanputte CL, Regan JL, Russo AF. Skeletal organization: Basic and joints. In: Seeley'due south Essentials of Anatomy & Physiology. 8th ed. USA: Mc Graw Loma; 2013. pp. 110-149 - 2.

Muscolino JE. Kinesiology the Skelatal System and Musculus Function. 2nd ed. New York: Elsevier Inc.; 2011 - 3.

Cashman KD, Ginty F. Bone. New York: Elsevier; 2003. pp. 1106-1112 - four.

OpenStax Higher. Anatomy & Physiology. Texas: Rice University; 2013. pp. 203-231 - 5.

Florencia-Silva R, Rodrigues Grand, Sasso-Cerri E, Simoes MJ, Cerri PS. Biology of bone tissue: Construction, role, and factors that influence bone cells. Biolmed Research International. 2015:ane-17 - 6.

Tim A. Bone Structure and Bone Remodelling. London: University College London; 2014 - vii.

Mohamed AM. Review article an overview of bone cells and their regulating. Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2008; 15 (1):four-12 - 8.

Akter F, Ibanez J. Os and cartilage tissue engineering. In: Akter F, editor. Tissue Engineering science Made Easy [Cyberspace]. 1st ed. New York: Elsevier Inc.; 2016. pp. 77-98. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-805361-iv.00008-4 - ix.

Guus van der Bie MD, editor. Morphological Anatomy from a Phenomenological Point of View. Rome: Louis Bolk Plant; 2012 - x.

Wojnar R. Bone and Cartilage–Its Structure and Concrete Properties.Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.; 2010 - 11.

Karaplis Ac. Embryonic evolution of bone and regulation of intramembranous and endochondral bone formation. In: Bilezikian J, Raisz L, Martin TJ, editors. Principles of Bone Biology. 3rd ed. New York: Academic Printing; 2008. pp. 53-84 - 12.

Dennis SC, Berkland CJ, Bonewald LF, Determore MS. Endochondral ossification for enhancing bone regeneration: Converging native ECM biomaterials and developmental engineering in vivo. Tissue Engineering science. Office B, Reviews. 2015; 21 (3):247-266 - 13.

Clarke B. Normal bone anatomy and physiology. Clinical Journal of the American Social club of Nephrology. 2008; 3 :131-139 - 14.

Provot S, Schipani E, Wu JY, Kronenberg H. Development of the skeleton. In: Marcus R, Dempster D, Cauley J, Feldman D, editors. Osteoporosis [Internet]. 4th ed. New York: Elsevier; 2013. pp. 97-126. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-415853-5.00006-half-dozen - fifteen.

Schindeler A, Mcdonald MM, Bokko P, Little DG. Bone remodeling during fracture repair: The cellular picture. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2008; 19 :459-466. DOI. x.1016/j.semcdb.2008.07.004 - 16.

Ozasa R, Matsugaki A, Isobe Y, Saku T, Yun H-Southward, Nakano T. Construction of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived oriented os matrix microstructure by using in vitro engineered anisotropic culture model. Journal of Biomedial Materials Research Part A. 2018; 106 :360-369 - 17.

Su P, Tian Y, Yang C, Ma X, Wang X. Mesenchymal stem cell migration during bone formation and bone diseases therapy. International Periodical of Molecular Sciences. 2018; nineteen :2343 - 18.

Wang 10, Wang Y, Gou W, Lu Q. Role of mesenchymal stem cells in bone regeneration and fracture repair: A review. International Orthopaedics. 2013; 37 :2491-2498 - 19.

Fakhry M, Hamade E, Badran B, Buchet R, Magne D. Molecular mechanisms of mesenchymal stalk prison cell differentiation towards osteoblasts. World Journal of Stem Cells. 2013; 5 (4):136-148

Submitted: September 12th, 2018 Reviewed: November 8th, 2018 Published: December 14th, 2018

© 2018 The Author(south). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution three.0 License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Source: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/64747

0 Response to "What type of cartilage is converted to bone?"

Post a Comment